How Did They Teach? Ideas from the Past about Keyboard Instruction

by Sandra Soderlund

Initially, the organ was the only “real” keyboard instrument. The smaller clavichord and harpsichord were developed as practice instruments for organists because playing the organ required having someone pump it for them.

M. de Saint Lambert – Les principes du clavecin, 1702

Stated that lessons were best begun when a student was a young child.

Francois Couperin – L’art de toucher le Clavecin, 1716

“One should not begin to teach notation to children until they have a certain number of pieces under their hands.” Believed that young children should not practice in the absence of the teacher. Carried the key to the instrument to prevent students from practicing without him, “lest they should undo in an instant what I have so carefully taught them.”

Jean Philippe Rameau – Preface to Pieces de clavecin, 1724

One of the first to recommend modern fingering.

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg – Die Kunst das Clavier zu spielen, 1750

Friend of the Bach family. Both French and German experience. Gives ideas on teaching children how to read music. Advocated for hands alone learning first, then together. To avoid the exercises being committed to memory, he suggested having new reading exercises every day. Wrote on different types of touch that could be used in playing. Addressed what we know as finger-pedaling (similar to Alberti bass patterns with a slur, which indicates that all the notes should be held).

J.S. Bach – Clavierbuchlein vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, 1720

A biography about Bach describes the style of his playing, emphasizing the touch that Bach used to play his instruments. He was very deliberate in teaching this touch to his students. In particular, they were required to practice all ornaments in both hands. The above book is the only one he himself wrote. It contains his famous chart of ornaments. The book still used early fingering, which seldom employed the thumb.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach – Versuch ober die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen, 1753

J.S. Bach’s son/protégé. He loved the big clavichord and began to stress the pianoforte. Three elements contributing to the art of playing:

1. Good fingering

2. Good embellishments.

3. Good performance.

Bach discussed the snap of the finger that produces a slight accentuation of the following note. An incredibly useful technique!

Daniel Gottlob Turk – Klavierschule, 1789

The clavichord is still seen as the primary teaching instrument, but the principles should be applied to the organ and now the pianoforte as well. The note following a suspension or appoggiatura should be played more softly. Dissonances should also be stressed.

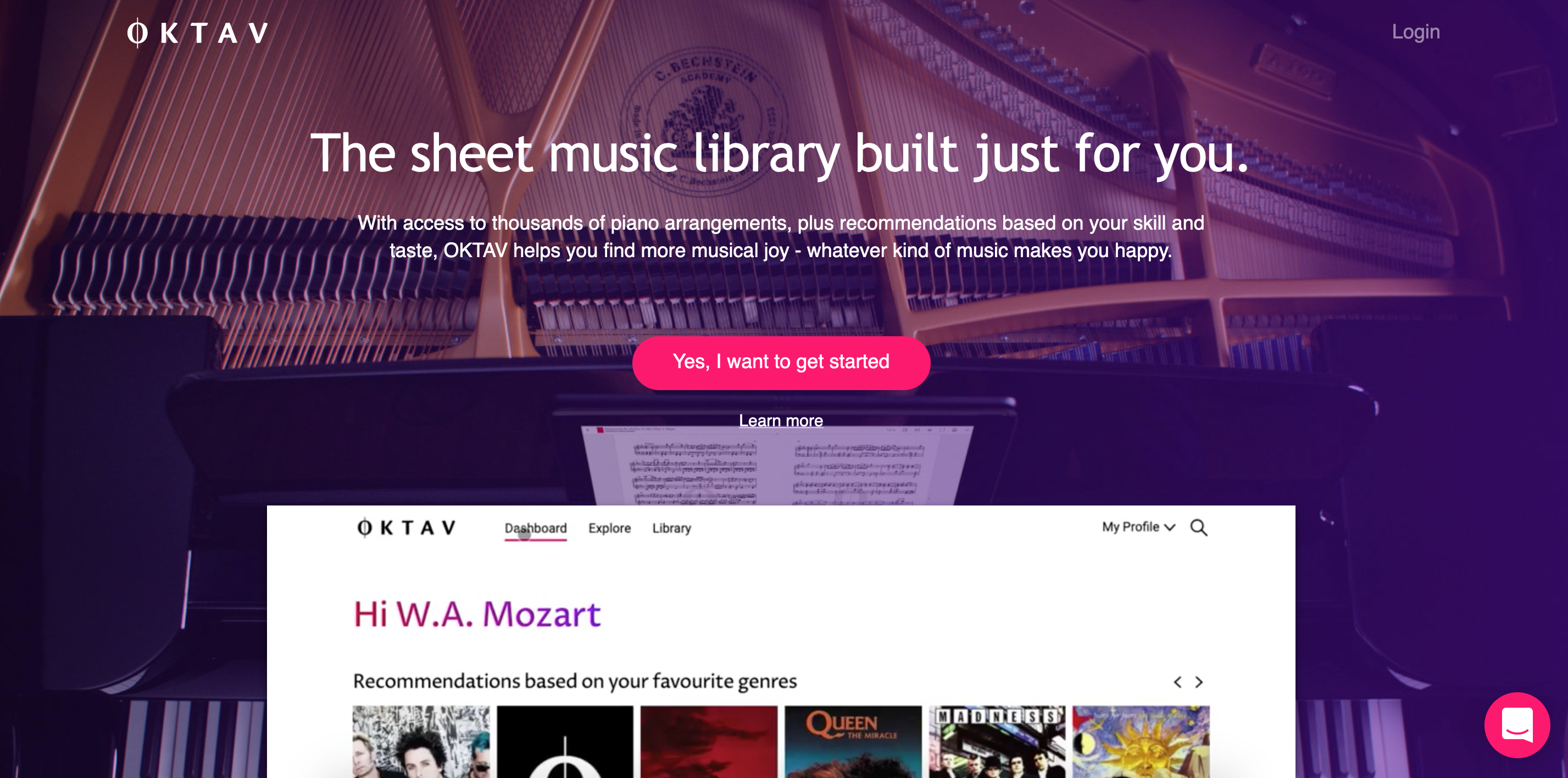

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

The Nannerl Notebook by Leopold Mozart contains a variety of technical exercises that were probably used in preparation for playing extemporaneous cadenzas. The Mozart Letters were recommended. Ms. Soderlund read several excerpts, which were often humorous. She then went on to play a Trill Exercise that she recommends to everyone and said that if you practice it every day with a very even rhythm, you’ll never have trouble with ornaments again. Hummel lived and studied with Mozart from age 11-13. It is probably from him that we get the Trill Exercise and several other Etudes.

Muzio Clementi – Introduction to the Art of Playing the Piano-forte, 1801

Clementi is considered the “father of the piano.” Clementi published music of many of the composers of his day and also built pianos (Ms. Soderlund has played one of his pianos and said that it was lovely!). He was the first to recommend legato as the normal touch. He describes three kinds of staccatos – wedge=1/4 value of the note; dot=1/2 value of the note; dot with a slur=3/4 value of the note.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Czerny studies with Beethoven. Beethoven agreed to take him on as a student, but insisted that he get C.P.E. Bach’s book on playing. Czerny later took over the teaching of Beethoven’s nephew, Karl. Beethoven encouraged Czerny to focus especially on interpretation of the music.

Felix Mendelssohn

Started the Leipzig Conservatory even though he himself didn’t teach a whole lot. At the age of ten, he wrote a fabulous work for two pianos. His sister, Fanny complained that her fourth and fifth fingers weren’t strong enough, so at the age of twelve he wrote an etude for her to help strengthen those fingers. It’s a killer!

Friedrich Wieck – Piano and Song, 1853

Friedrich was Clara Schumann’s father. Expressed that he tried to excite the pupil’s mind and teach neither too much, nor too little, during the lesson time. He also advocated teaching students by rote. From early on, he taught students harmony and had them play cadence patterns with figures. Pianists of this era could improvise very well because they practiced so many harmonic progressions and exercises that gave them the experience and technical skills they needed to improvise fluently. He stressed that scales should be practiced hands together until mastered. Another great idea he had was that a student always had one piece that was considered their “friend and companion.” They were to practice it every day so that it was fully mastered and could play at all times. He greatly disliked the pedal and minced no words in expressing his thoughts on the matter!

We ran out of time for the following composers/pedagogues that were included on the extensive handout. More information may be read in Ms. Soderlund’s book, How Did They Play? How Did They Teach?

Robert Schumann – Album for the Young, 1848

Frederic Chopin

Franz Liszt

Johannes Brahms

Anton Rubinstein: “Why are my pupils afraid of me? All I do is stand on their feet and scream at them.”

Claude Debussy

William Mason – Touch and Technic for Artistic Piano Playing, 1889, 1900-2.

The session concluded with Ms. Soderlund playing a lyrical one-finger etude by William Mason to illustrate syncopated pedaling.

Leave a Reply